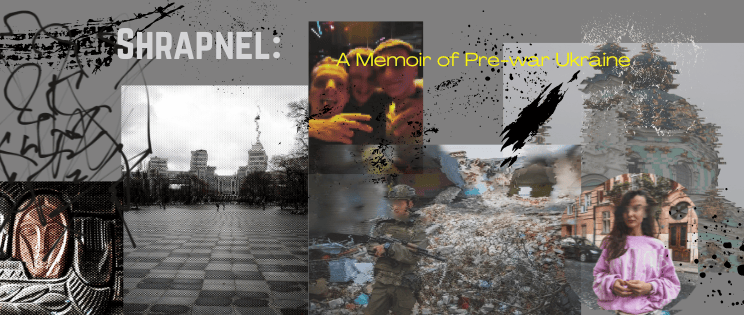

Shrapnel: A Memoir of Pre-War Ukraine

Delve into the heart of Ukraine through personal stories and reflections. 'Shrapnel: A Memoir to Pre-War Ukraine' offers insights into life before conflict. Join me on a travel blog that captures both the beauty and resilience of this remarkable and often misunderstood country.

Nick Dulepski

6/20/202515 min read

White Raven Lands

The plane touched down in Kyiv, and I felt the hum of a new beginning beneath my feet. I felt an immense sense of freedom after spending years working long hours doing odd jobs in the states. Now, I told myself, my destiny would be totally in my hands. Moving to Ukraine to teach English wasn’t a career change, it was going to be a reset for my life and my sense of who I was. It was September, 2021, and the city had enveloped me immediately with faded Soviet mosaics juxtaposed with towering new office buildings and the orderly vibrance of modern city life. My first trip abroad, and Ukraine was exceeding my wildest expectations.

The architecture was the first thing that got my attention. Gothic spires mingled with Baroque flourishes, and the golden domes of Orthodox Cathedrals caught the late afternoon sun, glittering like jewels. St. Andrew’s Cathedral, perched high above the city, its teal and gold a striking contrast against the sky, drew me in. I walked the winding, cobblestone path of Andriivs'kyi Descent, a bohemian artery pulsating with vendors, and the scent of street food (If you ever do visit Ukraine, eat as much food as you can. You can thank me later.). I remember looking around and thinking to myself “this is the part of the world everyone has been warning me about?”. What I was seeing wasn’t some depressed dystopia. It actually looked much happier than my Connecticut suburban home town.

I was so jet lagged on the first night that I found myself wide awake at about 2 am. In the early hours, I wandered out, taking solace in a 24-hour bar. I took a seat next to someone my age who was clearly having some kind of celebration with his friends. We'll call him Oleg.

“Are you American? What are you doing here?” Oleg asked.

“I needed something different. I took an English teaching job in Kharkiv. I’m in Kyiv for a couple of nights.” I replied.

“Welcome to my country!” Ukrainians are very hospitable. “I work in a call center and I talk to a lot of Americans. You are very good people!” Oleg exclaimed.

"Well, some of us." I replied. "Thank you Oleg, that's kind of you."

I hit it off with his friends as well. They were all working-class 20-somethings. While Oleg worked in the call center, his two friends were mechanics who worked on shipping vessels and had just returned from their last trek, Turkiye. They told me about some great things to see while I was in town and we drank. Oh boy, did we drink.

The night ended abruptly as we stepped out into the Kyiv air. A group of men emerged from the shadows. Dressed in all black, this group of Gopniks looked exactly how you'd imagine when I say "group of Gopniks". I couldn't understand what they were shouting about, but these were angry little Gopniks. My first "Slavic fist fight," as I would later call it, was quick and surprisingly, ended with me on my feet. As my new friends engaged in a 3-3 contest, I was freed up to deliver decisive punches or stomps which ended up being too much for them. I was not any good at fighting but found myself in the perfect situation to help. It was an abrupt, visceral introduction to a city that I had begged for an adventure and which had immediately given it to me.

Welcome to Kharkiv

Kyiv had made me a believer, but Kharkiv was my true destination. The city wasn't as polished as the capital; it felt more real, more raw. It was a city of stark contradictions. The colossal, grey Constructivist monolith of the Derzhprom building loomed over Freedom Square, casting a shadow of Soviet ambition, while nearby, the slick glass of tech hubs appeared almost borrowed from another world. Students from the city’s many universities absolutely blanketed the streets at night, resembling a monsoon of restless, youthful energy that was utterly infectious. The metro whisked you between these interwoven eras. On brand, its stations were ornate, though the trains themselves were in major need of a refresh. As I took in the city, feeling like I had struck gold, I prepared to start my journey as an English teacher.

My first day teaching teenagers, I fully expected all unholy hell to break loose. But it didn't. They were respectful, occasionally joking under their breath, and ultimately were very easy to manage. They saw my foreignness not as a barrier, but as a novelty to be explored, poking fun at my accent and teaching me wonderfully obscene Russian slang with mischievous grins. It was in the last class of my second day at the school, amidst the friendly clamor, that I saw Sofia. She sat near the back, not shy, but possessing a quiet, gravitational calm. This class hadn’t been put on my schedule and I pretty much had to bullshit my way through it. It was a nerve racking experience for a 25-year old me. I asked how the class had gone for them and Sofia very softly said “It was great. Thank you so much.” And with that my confidence was completely rebooted.

My teaching life was split. Afternoons were for the respectful, malleable teenagers. Mornings, I visited the surprisingly well-developed offices of Kharkiv's booming IT sector, teaching software teams how to better communicate with their foreign colleagues. They were all clustered around the Naukova metro station while the majority of the restaurants and smaller shops were in the “old” downtown, that metro station being Maidan Konstytutsii.

It was in the IT district that I met Oleks, the CEO of a web development agency. He was a towering man with a mind like a steel trap, a living embodiment of the post-Soviet transition. "In the nineties," he told me once, "I sold Soviet medals and Matryoshka dolls to tourists on the streets of Moscow.” Now, he created websites for major corporations, including the maker of the camera I had with me for this trip. This office was always stocked with rum, something I had never seen before in the states. Work hard, play hard I guess. When I talked to guys like Oleks, it was hard not to feel great admiration. This wasn't some nepotism baby or grifter. This was a real entrepreneur. A man who had actually pulled himself up by his bootstraps. And I increasingly found that the modern Kharkiv was being built by all kinds of people who possessed that indomitable spirit.

I found myself quickly endearing to the locals, making friends with a warmth I hadn't anticipated. Among them was Sofia. I think she had seen the obvious overwhelm in my eyes during those initial days and, for whatever reason, she took me under her wing. Sofia became my guide, leading me through the city's hidden alleys and bustling squares. She showed me the former home of one of the Soviet Union’s most famous singers, Lyudmila Gurchenko. She took me for my first bowl of borscht at a small, family-owned restaurant. We had a few nights walking together in Shevchenko park where I began to get to know the real Sofia. I thoroughly enjoyed these nights with her but it was anyone's guess how much she actually liked me. I sometimes felt like an instrument for her, a way to get information she needed by playing the right keys but she surely couldn't be as interested in me as I was in her. Still, it was with her that I felt the truest sense of adventure.

Sofia was more than just a guide; she in some ways was more compelling than the destination. Her beauty was undeniable, but it was her grace, the quiet confidence in her movements that took hold of me. She seemed to embody a lot of what I felt I lacked. When I slouched, she stood straight. Where I simply did enough, she would overachieve. There was a certain mystery to her as well. The speed at which we bonded and the occasional inability to understand each other's mannerism could lead to some uneasiness. But I always felt safe and seen with her. One evening, she invited me to her apartment. She sat down at her piano, her fingers hovering over the keys for a moment before she began to play. It was a classical piece, which matched her sophisticated demeanor. As music filled the room, her notes began to weave around me. I watched her, the gentle sway of her body, the focused intensity in her gaze, the effortless dance of her fingers across the keys. At that moment, I slipped into a trance. As I looked on and listened, I thought of waking up next to her, running my hands through her hair. It scared me how genuinely I wanted her in that moment - not just her body. I wondered what tectonic void in me I suddenly knew she could fix. It felt like a new space was opening in me. A space to get close to someone.

Turbulence

But as my world filled with light, darker figures began to move at its edges. Roy, an older American from Indiana, was the first. Roy had moved to Ukraine under mysterious pretenses and had marketed himself as a cowboy air dropped into Kharkiv. In the bars and restaurants along Sumska Street, he was treated like a minor celebrity. Waitresses knew his drink, bouncers nodded him through the line. This odd, doughy king somehow emphatically won the hearts and minds of this city.

He would always introduce me with a certain condescension, "This is my new guy. Fresh off the boat. I’ll coach him up." He did not. He commanded his environment with an air of grandiosity. He was a man so embedded in the local scene that he had become part of its fabric. It was this status, I would later realize, that made him impossible to bring down.

Something you instantly learned about Roy was that he couldn't stop talking about himself. He was hilarious, I'll give him that, but he would drone on for quite literally HOURS if you let him. Roy’s stories started as exaggerated tales of bar fights, each one more theatrical than the last.

“I lived in Louisiana for a few years and anyone who messed with me would pay the price. I’d give them a beating they’d never forget. However, I had to always keep moving because I couldn't stay out those fights. It was like I couldn't back down. I couldn't let things go.” he included in his marathon story-telling sessions.

Overtime, it slowly dawned on me that these weren't mere anecdotes but thinly veiled metaphors which he'd take progressively less care to hide their origins. They explained his nomadic lifestyle but I highly doubted he was roundhouse kicking himself out of one zip code to another. Then, one night, after a few too many drinks, the facade completely crumbled. Roy confessed, with a chilling lack of remorse, that he had done something terrible to one of his stepchildren back in the States and had never been caught. A cold dread settled in my stomach. Roy had recently taken in a new Ukrainian stepdaughter. The fear that he would assault her here, far from the reach of the law he had so easily evaded before, became a persistent knot in my gut. I cautiously broached the subject with a lawyer whose Airbnb I was renting at the time, asking what recourse I might have if I ever witnessed such an act. Her response was chillingly simple, delivered with a weary shrug: "If he has money, he will be fine." It was a confirmation of the grim reality I was beginning to suspect: Ukraine, for some, was a land of loopholes, a place where a Western passport and a thick wallet could buy a form of moral immunity. The conversation hit me like a truck. I realized that I had been naive. I was wrong. I can't just travel the world, see the good in people. Because inside of anyone there could lie a monster.

And then I met Chuck.

Tech, bro?

I ran into him at a bar for students in the basement of a commie block. It was the same bar where Roy absolutely smoked me in a game of pool before claiming he was the “state champion of pool in Indiana” which he is definitely not. He was younger, in his early twenties, and radiated an intense, just slightly off energy. He presented himself as a tech-savvy visionary, working on software development and aspiring to launch his own cryptocurrency. That first night I met him I watched him pull a wad of $9000 out of his sock. Naturally, I was intrigued. He was sharp, articulate, and seemed to embody the modern, forward-looking spirit I’d seen everywhere in Kharkiv’s tech scene. He told me that he was totally convinced that America would basically collapse by 2026 and wanted to put down roots somewhere with more traditional values. "He's trying to sound edgy" I told myself "but I'm glad he's seeing the world." Chuck went on to tell me that he was really close with his father who had taught English in Ukraine for a few years in his youth.

But I soon saw another side of him. Chuck treated the city’s nightlife like a hunting ground. He was a predator, but his method wasn't brute force; it was a relentless, high-volume numbers game. I watched him one night, moving through the crowd with a practiced, unnerving efficiency. He would approach a woman seemingly at random and deliver a rapid-fire series of lines from a well-rehearsed script. If he met the slightest resistance, he would have a salesman-like rebuttal to keep the conversation going. If it was truly a no, he’d move on to his next target without so much as a flinch. In a way I envied Chuck. He had the brains I didn’t, the confidence I didn’t, and certainly the girls. He was never connecting with people; he was processing data points with total detachment. I wondered if that was the secret, if life really was just a big numbers game. Oh, and this guy had a weird temper. He got the two of us kicked out of a hostel one night. I don’t know exactly what was said but apparently someone pushed his buttons and he let out something unforgivable in response. Things like that would happen with Chuck. It was like once he was out my sight he would morph and become completely intolerable. Knowing him, it had to be intentional, but it was beyond me what kept setting him off.

One night I brought up these falling outs and he seemed to have a response ready and waiting.

With the smirk of a 10-year old who just got out of doing their chores. "I don't worry about what these people think of me. They're not a developed people. I stick my nose up at them. Anyone who doesn't has a serious savior complex."

After a night of heavy drinking we ended up talking, sitting on a bench in the cool air outside the bar. I felt so comfortable with him. There’s something about finding a fellow American in a sea of foreigners that can bond you to someone like nothing else. The conversation drifted from tech to politics, then to history. And that’s when Chuck’s final mask came off. He started talking about the "purity" of Eastern Europe, praising its lack of diversity. He went on-and-on about something called the “selfish gene” and how western societies were being denigrated by ethnic waste. With a smile of pure delight, he confessed that he had deliberately sought out Ukraine, hoping to find other Western expats who shared his ideology. Chuck, it turned out, was a devoted Nazi, a virulent antisemite who viewed this country not as a culture to be experienced, but as a potential breeding ground for his hateful beliefs. I never met any Ukrainians who shared these beliefs but it seemed self-evident to me that Chuck was a part of a growing number of expats who were there to express beliefs that were taboo in the west. I could only hope that he wasn't the tip of the iceberg.

These encounters with Roy and then Chuck were enough to damage my perception of Ukraine. My life in Kharkiv had become a sickening paradox. On one hand, there was my profound affection for the people, for Sofia. There were the young families pushing strollers through Shevchenko Park, the weight of history etched into every building, the humble grace of everyday life. But on the other hand, there was this parasitic class of foreigners, men who saw Ukraine as a consequence-free zone—a place to indulge their perversions or incubate their ideologies. The city I loved and the city they exploited were the same physical space, and the cognitive dissonance was becoming unbearable. I was completely powerless as I watched a once beautiful dream of freedom curdle into a nightmare of debauchery.

A few weeks later I would run into Chuck again. Without any warning, he told me he'd be moving to Belarus.

“This country is all one big scam, my father warned me about it. I’m going to Belarus, Lukashenko actually cares about his people. The average IQ of a Ukrainian is 90.. 90! You should get out of here too man. You are better than this place” Chuck said, clearly fuming about something.

Anyone from Belarus can tell you objectively that Lukashenko doesn’t give a shit about his people, but maybe for people like Chuck he was just fine. I would’ve loved to delve into what exactly happened but my exponentially growing list of clients was taking all of my attention. Plus, by December, warnings from the State Department by text and email were getting more frequent. It was starting to look like a war might actually break out. The most surreal part of living in Ukraine just before the war is that absolutely no Ukrainian actually believed it would happen. Whenever I asked someone “What are you going to do if war breaks out?” they would laugh like I just told them an absurd joke. Despite all of the reports from western media, intelligence agencies, and very real troop movement by both Russia and Ukraine, absolutely no one for one solitary second believed that anything at all would happen. So for a while I simply let it fade into the background and went about my business as usual.

However, by February the warnings from the State Department had become incessant and the panicked phone calls from family back home had started pouring in. Reluctantly I packed my bags, and said the bittersweet goodbye to a life that had so quickly become home. I took the overnight train to Kyiv and boarded a plane to Krakow, Poland. It felt like a retreat. What happened in Krakow is for another story but I couldn't shake the gnawing that I had unfinished business in Ukraine. I told myself it would be temporary.

A week later, that world ended. War began.

The Adventure is dead...

Frantic calls and texts from my students detailed the escalating destruction. I just about had an out-of-body experience seeing how every single person I’d gotten to know was now being totally derailed by war. Tanks rolling by on their street, explosions waking them up, nephews volunteering to go to the front. Russia had invaded the country at warp speed and though they would soon be pushed back, at that time, the Russian army was knocking at the door of millions of innocent Ukrainians. My beloved metro stations had been turned into bomb shelters, later they would build makeshift schools in some of them. I saw a viral Instagram reel showing a building I had taught in just 3 weeks earlier being ripped to shreds by MLRS rockets. But I was waiting for one name more than any other. One night, it lit up. Sofia.

It was a video call. My heart leaped and sank at the same time. She was in her apartment, having come up from the basement shelter for a reckless glimpse of normalcy. She’d showered. She’d put on a little makeup. Her face showed no hint of exhaustion except when her eyes would glide downward as she’d start to get lost in the horror she had just been put through. "I miss you," she said, and the simple words carried the weight of a world burning to the ground.

We talked about trivial things—a book she was trying to read, a memory of our walk in Shevchenko Park. Though we didn't cover anything groundbreaking, it just felt so good to be with her again. For a few minutes, she was just Sofia, and I was just me. She was telling a small, funny story about her father's stubbornness, and a genuine, beautiful smile touched her lips. Her eyes, filled with that familiar warmth, met mine through the screen.

It was at that exact moment that I heard the impact of a Russian missile with my own ears for the first time. There's a certain menace to the horrible detonation which rocks everything around it. The initial, concussive hit is followed by the sounds of falling debris which, if in a residential area, drop with an eerie familiarity. A missile had struck the apartment building directly across the street from her. The noise nearly blew out my phone's speaker. Her eyes widened in terror and she let out a whimper. "I have to go," and the call abruptly ended.

The silence on my end was absolute. I sat there, staring at the black screen. I felt an anger at Russia, at their army. But I also felt a deep anger with myself. Despite how much I cared, how much I wanted to protect this girl, I hadn't the power to help her. In that moment, I found myself wishing I could switch places with her. I'd heard of those sort of sacrificial urges arising in high-stress situations but never thought I'd feel it myself. That was the last time I saw her in Ukraine.

Three months later, I saw Sofia in New York City. We met on the Brooklyn Bridge, thousands of indifferent witnesses strolled by our reunion. She wore a beautiful yellow sundress, a splash of defiant sunshine against the grey steel of the bridge. It seemed like a deliberate choice, an act of reclamation, a quiet insistence that she would not be defined by the darkness she had endured. She looked stunning, and I felt a pang of knowing that this was her intention: to plant a memory in my mind forever.

We walked and talked for hours. But there was a new space between us, an invisible wall of experience I could never breach. I could see her wrestling with things she wanted to say. Her sentences would start, then falter. She would look at me with these tortured eyes, I could never quite put my finger on what she was thinking. It looked like she wanted to tell me something so badly... but not as badly as she needed to keep it hidden. Perhaps telling me would've made her feel like an alien. Besides, what could saying anything do when you're going through the worst moment of your life and everything that you knew had just been taken away. We said goodbye at the foot of the bridge. As she walked away, I couldn't help but watch her every step. The only thing I wanted in that moment was to walk with her and go wherever she was going. I promised myself that I'd find a way to see her again. For reasons neither of us ever articulated, I never would.

I have spent years since constantly thinking about those people I met; the friends, the students, the city. I wonder about the invisible scars they must carry, the weight of what they endured. And I wonder, too, about Ukraine itself—if it will ever fully heal, if it will ever be a normal country. It’s a place where the shrapnel of its past and present seem to forever doom its future. Still, I can't wait to visit again.